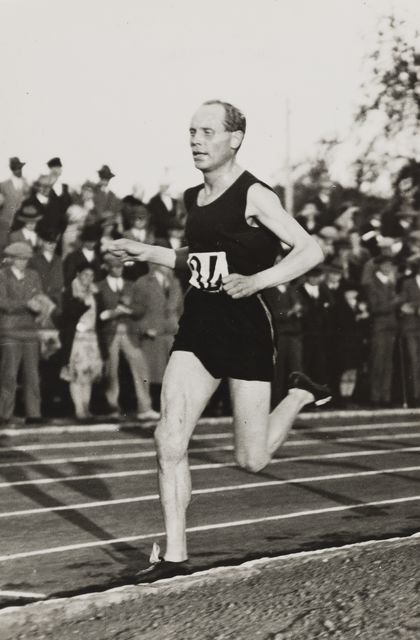

Paavo Nurmi – a running ambassador for Finland who embodied the nation’s aspirations towards Europe and the West

Paavo Nurmi (1897–1973), who won nine gold and three silver medals at Olympics, is one of the world’s most successful distance runners of all time. At the time, Nurmi’s superiority was astonishing. The modern Finland was embodied in Nurmi. The runner, who smashed records with a stopwatch in his hand, was a representation of Finland aspiring towards Europe and the West.

Nurmi participated in the Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Paris and Amsterdam. Thanks to his Olympic success, he became one of the most famous Finns in the 1920s and 1930s. Nurmi’s public image was marked by modernity. He would run around the track with a stopwatch in his hand, closely monitoring his pace.

During the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, the French newspaper Le Petit Parisien draw a comparison between the man and his watch: “The cogwheels in his stopwatch are like his legs, like his heart and lungs: tireless, unbreakable.” Nurmi made exceptional sports history by winning the 1500-metre and 5000-metre races within just two hours.

Superhuman king of runners

Nurmi was a pioneer of modern sport. Martti Jukola, the most famous sports journalist in Finland, estimates that Nurmi revolutionised the principles of sports practice with his demanding workout methods. Sports had become “a tough reformatory that seeks to develop in the individual the properties that are necessary for succeeding in the struggle of the modern stressful life.”

A central part in the Nurmi myth was that “with his iron will he turned his body into an infallible machine that functioned at the command of its lord and master.” This made him the “king of runners,” an enigmatic superhuman athlete, in whom everybody wanted to admire “the unfathomable human achievements of the machine made of flesh and bone.”

In Finland, Nurmi was depicted not so much as a particularly Finnish hero, but as an exceptional superhuman being. Nurmi, who monitored his lap times with a stopwatch in his hand, was a symbol of the modernisation of the nation rather than an embodiment of the national romantic idea of the frontiersmen’s Finland.

In the early years of independence, Finnish sport was marked by a division into two ideologically separated camps which operated under the auspices of the Finnish National Sports Federation (SVUL) and the Workers’ Sports Federation (TUL). Despite his humble working-class background, Nurmi competed under the conservative SVUL. He was nevertheless popular with members of the TUL, even though working-class athletes did not officially acknowledge the achievements of SVUL athletes. Nurmi’s acceptance among the TUL members was helped by the fact that Nurmi wrote about his sports experiences in working-class newspapers and periodicals.

Finland’s image builder comparable to Sibelius

Paavo Nurmi’s international reputation aroused a sense of pride in Finland. Newspapers characterised Nurmi as one of Finland’s best ambassadors abroad. Alongside Jean Sibelius, Nurmi was the most internationally renowned Finn in the interwar period.

Nurmi’s superiority appealed to people especially in the United States, where the runner went on tour in 1925 and 1929. The first tour in particular was a great success. Nurmi, who was in top form, was able to run from one victory to another. During the Winter War, his fame helped raise funds in North America for the Finnish cause.

The popularity of the runner in Finland is illustrated by the fact that already in 1924 the Finnish government commissioned a statue of him from Wäinö Aaltonen. The statue was included in the collections of the Finnish National Gallery (Ateneum). It was also exhibited in Stockholm (1927) and in Paris (1928). The statue’s fame was increased by the publicity efforts for the 1940 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. The poster shows Nurmi, cast in bronze, running against a backdrop of the globe. The same poster, slightly modified, was used in the 1952 Games.

In addition to the original artwork stored in Ateneum, four additional casts have been made of the Nurmi statue. The first copy was placed in the vicinity of the Olympic Stadium before the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki. The statue can also be admired at the Lausanne Olympic Park managed by the International Olympic Committee, in front of the Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä, and in Turku, Nurmi’s hometown.

Success requires work, work and work

Paavo Nurmi was a highly analytical top athlete. He did not accept that the main factors explaining the success of Finnish long-distance runners were sauna and sisu. According to Nurmi, competitive sports in the 1920s and 1930s had reached such an advanced level that victories could no longer “be achieved with good luck and marvelous gifts.”

“No, it takes a tremendous amount of work. An elite class athlete must pass three stages before reaching the top: the first stage is hard work, the second stage is hard work, and the third stage is hard work. Of course, it is an excellent thing if the athlete also has innate talent.”

Nurmi took a pragmatic view on monetary rewards paid to top runners. After his 1925 American tour, he stated that strict compliance with the amateur rules clashed with Finland’s objective to attract international attention to the country through sports success. Nurmi’s monetary rewards created the foundation of his capital, which later grew, first thanks to investments in shares and then as his construction company and clothing business thrived.

Nurmi is made cautionary example of professionalism

Since the beginning of the 1920s, rumours had been circulating about the monetary rewards received by Paavo Nurmi. Nurmi was not only the most watched athlete of his time, but also the one who was most suspected of secretly being a professional. The Finnish track and field leaders were well aware of Nurmi’s cash prizes in the early 1930s. They feared that the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) would take action.

Their fears came true in 1932. The IAAF banned Nurmi, who was thus excluded from the marathon in the Los Angeles Olympics. A popular theory in Finland claims that Nurmi’s competition ban was the result of a personal witch hunt by the IAAF’s Swedish Chairman J. Sigfrid Edström. In fact, it had more to do with the IAAF adopting a tighter approach. The organisation was defending its position as an international monopoly in athletics in the early 1930s against increased efforts towards professionalism. Finding Nurmi a professional fitted that agenda well.

Nurmi continued his running career as a “national amateur” for a couple of years. After that, he coached Finnish distance runners for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Nurmi is also remembered as the final torchbearer of the torch relay and the lighter of the Olympic flame at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki.

In the final years of his life, Nurmi suffered from cardiovascular problems. The sports legend, who had gathered wealth through his business activities, founded a cardiovascular research fund in his hometown, Turku, in 1968. Nurmi’s childhood home has been converted into a museum.

Link:

Paavo Nurmi. The Official Site of the Flying Finn. The Sports Museum of Finland.

Literature:

Paavo Karikko & Mauno Koski. 2006. Legendary Runner. A Biography of Paavo Nurmi. The Sports Museum of Finland.