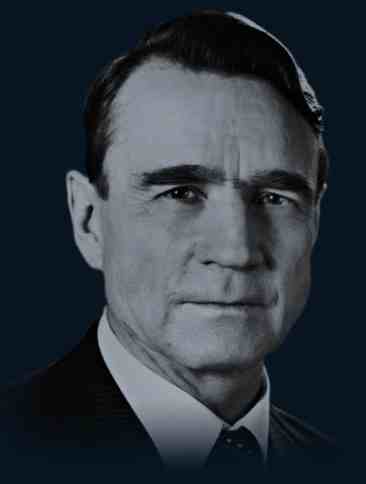

Patriot, supporter of parliamentarism, opener of the EU door

During the presidential term of Dr. Mauno Koivisto, Finnish parliamentarism stabilised and Finland became a member of the European Union. Koivisto served as President of Finland for two terms, from 1982 to 1994, and twice as Prime Minister, from 1968 to 1970 and 1979 to 1982. Apart from his political career, he was a labourer, a sociologist and a banker. He served as the Managing Director of the Helsinki Workers’ Savings Bank in 1959–1967 and was Chairman of the Bank of Finland’s Board of Directors, i.e. the Bank’s Governor, from 1968 to 1982.

Koivisto’s early years

Mauno Henrik Koivisto was born on 25 November 1923 in Turku. His father Juho Koivisto was a carpenter, a patriot and a deeply religious man. Mauno had an older brother and a younger sister. His mother, Hymni Sofia Eskola, died when Mauno was ten. The family lived in a small one-bedroom apartment in the centre of Turku. Mauno attended six classes of primary school before the war and finished his secondary school after the war. He earned money as a carpenter, as an errand boy at a book store, and as a helper at the Crichton-Vulkan shipyard and at a factory of Suomen Pultti.

During the Winter War Koivisto was in a fire brigade, putting out fires started by Russian incendiary bombs. Koivisto was seventeen when he volunteered for the Continuation War in 1941, first as a firefighter, then as a soldier. He participated in military action in the ranks of the 35th Infantry Regiment in Maaselkä and in a Jäger Company led by Lauri Törni in 1944. This company carried out counter-strikes and operated behind enemy lines. After the battle of Kuusiniemi, Koivisto was given the Russian Degtyaryov light machine gun as his weapon. The machine gun is on display at the Military Museum in Helsinki. During the war, Koivisto was promoted to the rank of corporal.

Koivisto joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1947. In that same year, he started writing columns under the pseudonym “Puumies” in the Sosialisti newspaper (later, Turun Päivälehti) edited by Rafael Paasio, MP. According to Puumies, “the communists are the greatest threat to our liberty and independence.” At the time of the so-called Leino strikes, Koivisto wrote: “There is no compromise between democracy and dictatorship, peace and terror.” He also participated in breaking the illegal political strike organised by the communists at the port of Hanko in 1949.

Talented and hard-working Koivisto took evening classes and passed his matriculation examination in 1949 while working at ports and construction sites. Language skills improved in summer jobs in Sweden and Britain. He was then admitted to the University of Turku, where he studied sociology, economics, political sciences and education. In 1951, he quit work at the port of Turku, after which he worked for two years as a primary school teacher. He graduated from the university as a Bachelor of Arts and licentiate in 1953 and, three years later, completed his doctoral thesis, which examined social relations in the Turku dockyards. Koivisto’s feat – from dockyards labourer to PhD – brought him nationwide fame, and the Finnish annual Mitä, missä, milloin elected him “The Name of the Year”.

Mauno Koivisto and Tellervo Kankaanranta were married in 1952. Assi, their daughter, was born in 1957. Tellervo Koivisto, a graduate of economics, later served as a Member of the Parliament and Helsinki City Councilor. She was also voted to the electoral college for the 1982 presidential election, earning 50,643 votes, which is an all-time record. However, as her husband became President of Finland, she had to leave all her political mandates.

Banker in politics

After two years of teaching, Koivisto served as a vocational counselor of the City of Turku, where he developed a scoring system for the selection of students to Turku vocational school. The system was in use until the 1970s. Koivisto contributed to the social debate in the press, renouncing ideological radicalism and emphasising that the goal of the labour movement should be to achieve relative improvements: “more, better and more secure.”

In 1957, Koivisto was elected as Director and, two years later, as Managing Director of the Helsinki Workers’ Savings Bank, which at the time became the largest Savings Bank in Finland. He carried out reforms in the bank, e.g. in the fields of housing and hire-purchase loans. During Koivisto’s ten-year period at the bank, its market share grew and its deposits in 1967 were 30 per cent higher than those of the second-largest savings bank.

Koivisto’s banking career came to an end as he was appointed Minister of Finance in a cabinet led by Rafael Paasio in 1966. Both the government and the parliament had a leftist majority. In domestic policy, the balance of power was about to swing in the SDP’s favour, as the party and the trade union movement were starting to heal after years of division. From now on, Koivisto was constantly in a dual role: he was a politician and a banker. In opinion polls for potential successor candidates for President Urho Kekkonen, Koivisto was a perennial favourite.

In 1967, Koivisto was appointed as General Manager of Elanto, but already during the same year he was elected to succeed Klaus Waris as Governor of the Bank of Finland. He could not accept the position immediately, as he became Prime Minister after Paasio in 1968. Koivisto was the “godfather” of two very comprehensive economic and incomes policy solutions, the so-called Liinamaa I and II.

On his ideology, Koivisto has said as follows: “The birth and rise of social democracy has taken place within capitalism: there must first exist a functioning market economy, there must exist forces to control, and income to distribute.”

Friction between Koivisto and Kekkonen

Prime Minister Koivisto and President Kekkonen fell out for the first time when Koivisto’s government was forced to withdraw from the planned Nordic customs union Nordek. Officially, the dispute was about the exit strategy, but the real reason was Kekkonen’s and Karjalainen’s desire to use the Finnish-Soviet relations against Koivisto. Koivisto’s foreign policy opponents used Nordek to prove that Koivisto “did not understand” how Soviet relations should be handled or even that he did not “enjoy the Soviet Union’s confidence”, which was considered a necessary prerequisite for the country’s leadership positions.

After the 1970 elections, Koivisto withdrew from the political scene to carry out the duties of the Governor of the Bank of Finland, but when Rafael Paasio formed the SDP-led minority government in February 1972, Koivisto became Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance. Koivisto would have been a strong presidential candidate for his party that same year, but Kekkonen had decided to continue as president. To secure his election in April 1972, Kekkonen had recourse to an emergency law to completely bypass the elections for the electoral college, thus eliminating any rival candidates.

Koivisto sought to establish a free trade agreement between Finland and the EEC, but noting that Kekkonen was not willing to back the agreement, Koivisto advised Paasio’s minority government to resign in July 1972. One of the underlying reasons for this was the SDP’s fear that, once again, they would be sidetracked from Finnish foreign politics.

In September 1972, president Kekkonen appointed SDP party secretary Kalevi Sorsa as Prime Minister of a majority government. Koivisto was not offered a ministerial position. Kekkonen, as the true leader of Sorsa’s and many other governments, often criticised the tight monetary policy of the Bank of Finland under Koivisto. For example, when he forced the parties – in a live TV broadcast in November 1975 – to form the so-called emergency government, Kekkonen blamed Koivisto and the Bank of Finland for the country’s difficulties.

Towards presidency

Before the 1979 parliamentary election, SDP Chairman Kalevi Sorsa came to the conclusion that “no responsible party leadership can squander such an asset” as the public popularity of Mauno Koivisto. The party named Koivisto Prime Minister after the election, with the aim to make him the president after Kekkonen.

Government collaboration between the SDP and the Centre Party was a continuous battle for the future presidential position. The Centre Party, under the leadership of Paavo Väyrynen, attempted to bring Koivisto down. Koivisto’s survival tactic was “keeping a low profile”, which he described in his book Politiikkaa ja politikointia (“Politics and politicking”).

The battle between Kekkonen and Koivisto saw a dramatic twist when Kekkonen tried to topple Koivisto’s government in April 1981. During his presidency of a quarter of a century, Kekkonen was accustomed to change governments and ministers.

However, Prime Minister Koivisto had secured a majority within the government as well as the parliament’s support and refused to step down. He appealed to the Constitution, which rules that the government can continue as long as it enjoys the trust of the parliament. Koivisto’s successful defiance of Kekkonen placed him immediately in the political focus.

Five months later, Kekkonen’s health failed and he first went on sick leave and then resigned from the presidency. As Prime Minister, Koivisto became acting president, which strengthened his position in the early presidential election. In the electoral election, Koivisto received 146 of the electorate of 300 and was elected in the first round with 167 votes, as the majority of the electors for Kalevi Kivistö (SKDL) voted for Koivisto.

New era of parliamentarism

Koivisto began his term by assuring domestic and foreign skeptics that he was able to continue the Paasikivi–Kekkonen foreign policy doctrine. The doctrine emphasised the importance of the Soviet relations and the continuity of the rituals related to the Finno-Soviet YYA treaty of 1948, as well as contacts with the representatives of the Soviet security agency KGB.

However, a major change in the Finnish political system took place in 1983. Without changing a letter in the constitution, Finland took one giant leap to normal parliamentarism. During Koivisto’s presidency, the parliament was never dissolved (the last times were in 1971 and 1975), nor has it been dissolved ever since: the governments have had a majority in the parliament and have sat throughout the electoral term and all parliamentary parties have been eligible for the government. Until then, the governments had lived for one year only, on average.

Koivisto brought about this change by adopting a different presidential role than his predecessors. “I think it is safest that the pyramid rests on its base and not on its apex; it is best not to concentrate too much power to one man,” Koivisto said before the 1988 presidential election.

He was elected for a second term in the first round by 189 votes, as, in addition to his own 144 electorate, a significant proportion of Harri Holkeri’s electorate voted for Koivisto. It says something about the “Koivisto phenomenon” that 86.8 per cent of those entitled to vote voted in the election, which is an all-time record.

Piloting Finland through European turbulence

In terms of foreign policy, Koivisto’s first term, according to his own words, was largely about “maintaining, fine-tuning and updating the initiatives made by Urho Kekkonen.” On the other hand, he observed a need to “strike a greater balance between lofty speeches and people’s everyday lives.”

During Koivisto’s second term, Finland faced surprising and dramatic changes in Europe in 1989–1995. German reunification, the collapse of communism and dissolution of the Soviet Union, the disbanding of the Warsaw Pact and the newly gained independence of its member states, as well as the transformation of the European Economic Community into the European Union, and its subsequent expansion, created a whole new international political environment for Finland.

Koivisto’s approach, after the conditions in Europe began to change, can be characterised as cautious but determined. The fact that the presidents of the United States and the Soviet Union held a summit in Helsinki in September 1990 is testament to the appreciation enjoyed by Koivisto and Finland. After the Soviet Union was dissolved a year later, Finland broke out of the Finno-Soviet (YYA) treaty, which had dominated the country’s foreign policy throughout the post-war era.

As the EEC opened its doors to expansion, Finland first signed the Agreement on the EEA (European Economic Area), applied for full membership in the European Union, and welcomed NATO’s offer to join the Partnership in Peace programme.

Volleyball and philosophy

Koivisto’s charisma and popularity were based, in addition to his large knowledge and expertise, on his modest lifestyle, his volleyball hobby and his confident trailblazer approach, which was reflected e.g. at his summer place in Tähtelä, Inkoo.

Koivisto had the ability to use original language and create catchy phrases like “you should not be provoked when provoked.” He was a man who was able to create a sense of security and even faith in the future by saying that “the situation may look bad now, but it will look even worse in the future.”