The Games of the Fifth Olympiad in Stockholm were a great success for Finland. The Finnish team of 164 athletes won 9 gold, 8 silver and 9 bronze medals, 26 medals in total. The excellent result was largely based on athletics and wrestling. Athletes brought home 13 medals and wrestlers 7.

Hannes Kolehmainen, the Finnish long-distance runner, won three gold medals and one silver. His victory over the French Jean Bouin in the 5000-metre race was one of the most attention-catching competitions at the Stockholm Games. Kolehmainen set a new world record of 14:36.6 in the final race.

The Finnish achievements attracted widespread attention in Europe and North America. The modern Olympics, which had been organised since 1896, had become a major international event by the 1912 Games in Stockholm. Twenty-eight nations and 2,400 competitors competed in the Games. In addition to Swedish newspapers, 444 foreign journalists reported on the event, served by a Press Centre and good telegraph connections.

Great Britain and the eastern parts of the United States sent the largest teams of reporters. Sixteen reporters, including one female journalist, attended from Finland. Thanks to the telegraph connection, the results were quickly reported to Finland, where large crowds gathered outside newspaper offices to hear the news as soon as it arrived. Events were also recorded on film and the first glimpses of the Olympics were seen in Helsinki already during the Games.

Finland – a strong sports nation

Finland’s excellent performance in the Olympics brought international visibility, which was enhanced by the role of sport as a measure of the balance of power between nations before the First World War. In the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, the struggle between Great Britain and the United States received the largest press attention. In the Stockholm Games, the competition between the nations was further emphasised. Sweden had prepared carefully and ranked second in the medal table after the United States. Finland came fourth after Great Britain.

State leaders and the press compared the vitality of the nations based on their respective performances at the Olympics. The United States and Sweden, the two top countries in the medal table, appeared as strong nations. In contrast, Great Britain, France, Germany and Russia performed poorly in relation to population size. All these four countries increased their efforts in sports to ensure success at the 1916 Olympics in Berlin.

The medal statistics provided a favourable picture of Finland. The international press interpreted that the rural society had avoided the disadvantages of urbanisation and industrialisation. The Finnish interpretation was that the medals proved that Finland belonged to the civilised Western world, unlike Russia, which had only won five medals.

Finland’s participation was enabled by Coubertin’s sports geography

Finland’s Olympic participation was based on the privilege granted by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1907 to five non-independent sporting nations. The criteria for this special treatment advocated by the IOC President Pierre de Coubertin included a high level of sports culture, separate administration and legislation, and belonging to only one state. In addition to Finland, Olympic eligibility was granted to Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), Bohemia, South Africa and Canada. Poland and Catalonia, on the other hand, were not allowed to participate. The Olympics provided Finland with another opportunity to highlight its special position in the Russian Empire. Finland participated as a national team (separate from Russia) at the 1908 London Games and won a total of five medals. Verner Weckman, the wrestler, was the first Finnish Olympic gold medalist.

As the Olympics in Stockholm were approaching, both the Finns and Russians recognised the value the Games had in terms of international attention. Russia, which had tightened its grip on Finland, sought to prevent the participation of the Grand Duchy as an independent nation. Sweden and the IOC did not give in to Russia’s demands. Austria-Hungary, too, imposed conditions for the participation of Bohemia. Finland and Bohemia were allowed to participate, but not under their own flags. The compromise reached by Sweden, Russia and the IOC spared the Finns the debate over which flag to use. The Grand Duchy of Finland had no official flag. To honour a medal won by a Finn, both the Russian tricolor and a blue and white banner were raised immediately after the competition. Prizes were presented by King Gustav V only on the final day of the Games. This took place without the flag-raising ceremony.

Deliberate provocation at the opening ceremony

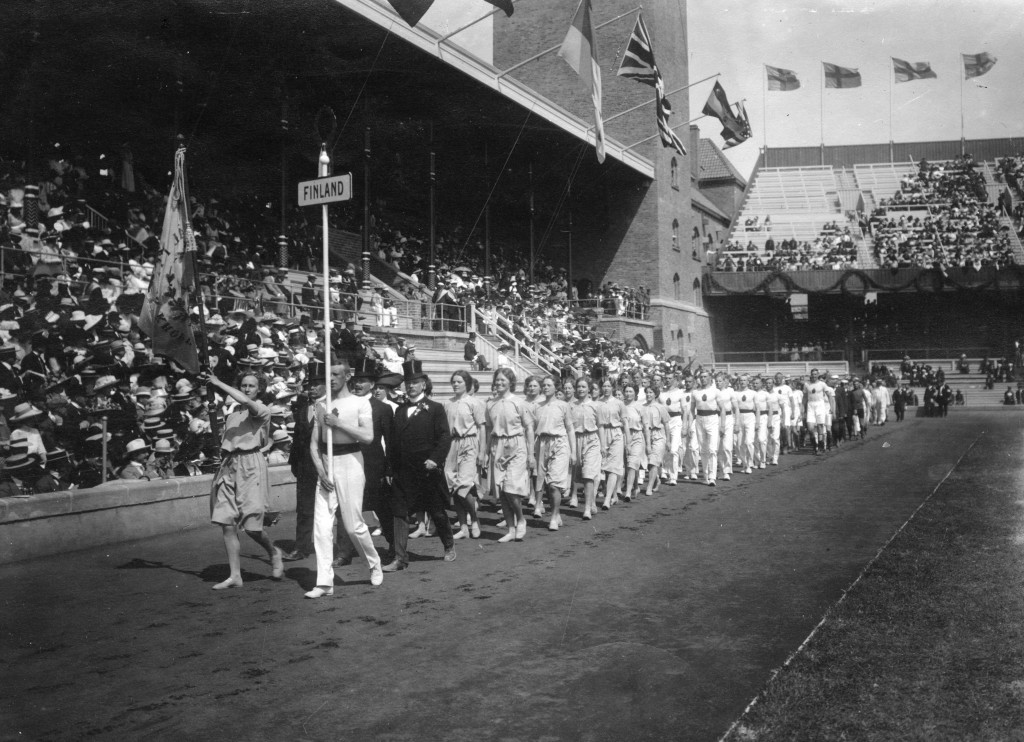

At the opening ceremony of the Stockholm Games the Finnish team arrived at the stadium behind the blue and white flag of the Helsinki Women’s Gymnastic Club, which was a deliberate provocation by the team. The flag was removed at the request of the Finnish member of the IOC, R. F. von Willebrand, because its use was in breach of the agreement concerning the opening ceremony. When the Finns left the stadium, they did not have any flag. The team’s competition outfits had on them the lion coat of arms of the Grand Duchy, which each athlete himself had made according to instructions from the Finnish Olympic Committee. The Committee funded the Olympic trip with donations received from companies and private citizens, as the highest representative of the Russian Empire in Finland, Governor-General F. A. Seyn, denied a fundraising lottery.

The international attention received by Finland irritated the leadership of the Empire. Russia and Austria-Hungary managed to have Finland and Bohemia’s special status in the Olympic Movement revoked in June 1914. Russia offered Finnish athletes the opportunity to take part in the Berlin Games in the Russian Team, but the Finnish athletes were reluctant to do that. In Finland, the IOC’s decision was seen as another indication of the Russification policy. The Berlin Games were cancelled because of the World War, and Finnish athletes never had to decide whether to participate in the Games as members of the Russian team. In the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Finland participated as an independent state.

Impulse for independence?

Of all the wins achieved in Stockholm the contemporaries attached the greatest symbolic value to the tight finish of the 5000-metre race. Uusi Suometar wrote that “that one metre by Hannes Kolehmainen makes Finland more widely known around the world than any extensive long-term projects.”

Lauri Pihkala, the sports ideologist, argued still in the 1950s that the Olympic success gave a decisive boost to the Finnish independence movement. According to Pihkala, Hannes Kolehmainen’s 5000-metre victory boosted Finland’s independence more than any single work of fiction.

Stockholm provided an excellent chapter in the great narrative of the Finnish independence. Between the World Wars, a phrase was adopted that Finland was run on the world map in 1912 in Stockholm. The narrative took its final form in autumn 1939, just before the Winter War. Martti Jukola, the sports reporter, announced in the October issue of Suomen Urheilulehti (a sports magazine) that Hannes Kolehmainen had run Finland onto the world map. After the Winter War broke out, Helsingin Sanomat published a drawing by Arvo Tigerstedt in which Kolehmainen is depicted running on top of the globe. The same motif is repeated on the Helsinki Olympics poster, where the globe is at Paavo Nurmi’s feet.

During the early years of Finland’s independence, the flag episode at the opening ceremony was what Finns best remembered of the Stockholm Games. In the stories that were told, the club banner was often replaced by the blue cross flag which, however, did not exist as an official symbol in 1912. This interpretation gained popularity during the Second World War, when the Finnish war propaganda listed acts of repression carried out by Russia at different times.