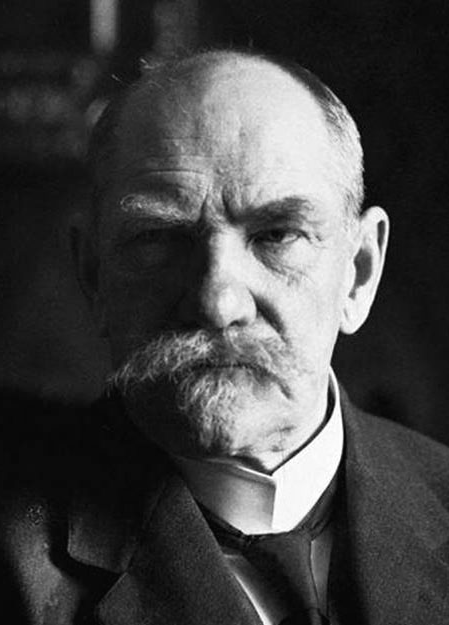

P. E. Svinhufvud – a lawyer, a supporter of Finnish independence, a defender of democracy

P. E. Svinhufvud (1861–1944) was a key contributor to the achievement and consolidation of Finnish statehood in three different stages of history. He was the most prominent figure in the legal battle of the early 20th century that led to the separation from Russia. He led the 1917–1918 government which issued the declaration of independence and obtained international recognition for it. He also had to overthrow a socialist revolution in a tragic civil war. After that, he was elected independent Finland’s first head of state in May 1918.

In the early 1930s, Svinhufvud saved the Finnish democracy. First, as prime minister and then president, he led the government that put into force anti-communist laws. Then he had to stifle the right-wing radicalism which had almost escalated into rebellion and involved illegal activities. He directed Finland’s foreign policy to the path of Nordic cooperation. As President of Finland, from 1931 to 1937, P. E. Svinhufvud maintained democracy and the rule of law and established in Finland a president-parliamentary system at a time when many European countries became dictatorships.

Defender of rule of law

Pehr Evind Svinhufvud had a tragic family background: his father, a sea captain, drowned in the Greek archipelago when Pehr was a small boy and a few years later his grandfather lost the family mansion and shot himself. The mother, Olga (von Becker), left alone with two small children, moved to Helsinki and secured an office job.

Svinhufvud made his professional career as a lawyer. He first graduated as a Bachelor of Arts majoring in history and then as a lawyer in 1886. He served as an official in the Senate’s law-drafting committee for eight years and at the Turku Court of Appeal for nine years. The Russian Governor-General dismissed him and a number of his colleagues in 1903 because they refused to agree to the political guidance of the court.

Svinhufvud then worked as a lawyer. In one prominent case in 1905, he was defence lawyer to the murderer of the Finnish Procurator (Chancellor of Justice) who had been regarded as too much of a Russophile.

As a nobleman, Svinhufvud had attended the Riksdag of the Estates as the head of his family. The year 1907 saw a radical electoral and parliamentary reform in Finland, in which, for the first time in the world, universal suffrage (right to vote) and eligibility was implemented to include women. Svinhufvud was elected to the new unicameral parliament as a representative of the Young Finnish Party. The party was socially liberal and reformist and defended the rights of the Finnish-speaking majority in the country at a time when Swedish was still the language of the ruling class.

The Young Finnish Party differed from the Finnish Party in that it demanded stricter constitutionalism and practised passive resistance and disobedience against Russification measures. This political line was not a new one but a continuation of the decades-long efforts of Finnish lawmakers to strengthen Finland’s special position and privileges as an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire by interpreting the declarations of the Emperor as binding constitutional laws.

Svinhufvud was elected Speaker of the new unicameral parliament for 1907–1913. He was elected even though the Young Finns were only the third largest party because the largest party, the Social Democrats, did not want to appoint their own candidate and they considered Svinhufvud to be the best non-socialist candidate. As Speaker, Svinhufvud defied the Russian Emperor as he viewed that the Emperor acted against the constitutional laws of Finland. As a result, the Emperor dissolved the parliament many times, but Svinhufvud was always re-elected as Speaker. He became the most prominent figure in the Finnish judicial battle against Russification.

Svinhufvud worked as a district judge in the countryside for eight years from 1906 to 1914, living first in Heinola and then from 1908 on in Luumäki. Kotkaniemi in Luumäki became a permanent home for him and his wife and their six children. The place is now a museum.

Exiled to Siberia

The First World War broke out in the summer of 1914, which affected Finland’s autonomy. Finland was turned into a Russian war camp governed by martial law. As judge, Svinhufvud refused to comply with the regulations he considered illegal. As a result, he was arrested in November 1914 in the Luumäki District Court. Governor-General Franz Albert Seyn exiled him “to Tomsk Oblast for as long as there is a state of war in Finland.”

While Russia sought to narrow down and end the autonomy of Finland, the Finnish politicians dreaming of independence pinned their hopes on Russia’s enemy, Germany. Svinhufvud believed that he would return from Siberia “with the help of God – and Hindenburg.” The German field marshal had just led his armies to a victory over the Russian troops in East Prussia. Two thousand young Finnish men volunteered for military training in Germany. They are called the Jäger movement.

Svinhufvud was not a prisoner in Siberia, but in exile, meaning that he lived freely at his own expense, first for six months in Tymskoye, a village of 200 residents, and then in the small town of Kolyvan. Svinhufvud’s exile lasted for two years and four months until the March (February) Revolution in Russia in 1917 enabled him to return to Finland.

Independence man

Svinhufvud arrived in Helsinki at the end of March 1917 as a celebrated national hero. The Social Democrats had a majority in the parliament, thanks to a win in the elections in the previous year. A Senate led by Social Democrat Oskari Tokoi had been formed in late March. The coalition government consisted of six Social Democrats, two Old Finns, two Young Finns, and one senator from the Agrarian League and one from the Swedish People’s Party. At the beginning of April, Svinhufvud was appointed Procurator, or Chancellor of Justice.

As Procurator, Svinhufvud found himself in the midst of a fierce political struggle which was first about Finland’s relationship with the Russian Empire and then the Finnish social system. During the summer, the radicalisation among the Social Democrats increased and political confrontation in Finland came to a head. When the Russian provisional government dissolved the socialist-majority parliament at the end of July 1917, the left thought it was some kind of ruse hatched by the centre-right parties. In the autumn elections, the Social Democrats lost their absolute majority, which accelerated radicalisation in the party.

The Socialists resigned from Tokoi’s Senate at the beginning of September, and for a while the country was ruled by a Senate led by E. N. Setälä from the Young Finns. On the morning of 7 November 1917, Prime Minister Setälä stated that the union between Finland and Russia had been severed, as the unrest in St. Petersburg escalated into street battles.

Until then, the Finnish authorities had recognised Russia’s supreme ruler, first the Emperor and then the provisional government, as the head of state of Finland. After Setälä’s statement, they did not do so anymore. Finland started to organise the so-called “highest authority”, i.e. the powers of the head of state, which until now had belonged to the Emperor. An attempt was first made to elect three State Regents, but when that failed, the parliament declared itself the highest authority on 15 November 1917.

At the same time, there was a general strike in the country, the Social Democrats appointed a Revolutionary Government, and armed Red Guards were occupying Helsinki and other cities. However, the revolution was called off and the strike came to an end on 18 November.

PM went underground in Helsinki

Svinhufvud was elected Chairman of the Senate (Prime Minister) on 27 November. The beginning of the Svinhufvud Senate was marked by internal confrontations. Finland was proclaimed independent and recognition for the independence was first sought from Russia.

Finland was now independent, but there were still 75,000 Russian soldiers in the country. Finland did not have an army of its own. The Senate started negotiations and preparations for the deportation of the Russian soldiers. At the end of January 1918, there were some 400 local chapters of the private White Guard in the country, with 38,000 members. The militant left had been systematically setting up Red Guard units since October, and there were now 375 of these units with some 30,000 members in them.

Authorised by the parliament on 12 January, the Svinhufvud Senate started to establish an authority that would maintain law and order in the country. On 16 January, the Senate appointed General Gustaf Mannerheim, who had returned from Russia in December, in command of the White Guards in Ostrobothnia. On 25 January, the Senate proclaimed the White Guards as government troops. The Senate also asked Germany to send back the Finnish Jäger battalion that had been there in training and on combat missions and send other military aid as well.

Disaster struck in late January: the biggest party in the country, the Social Democrats, started an armed rebellion on 26 January 1918. The Red Guards and the rebel government, the People’s Delegation, led by the former Speaker of Parliament, Kullervo Manner, very quickly captured Helsinki (the capital), Turku, Tampere, Vyborg and all of Southern Finland. Some of the Russian military in Finland supported the coup.

Prime Minister Svinhufvud and six other Senators, in fear of their lives, hid in Helsinki to avoid arrest. Four Senators had managed to move to Vaasa just before the revolution, where they re-established Government. The Svinhufvud government made two vital decisions: the legitimate government will not surrender, and it intends to defeat the rebellion by all available means. Svinhufvud’s leadership, his unfaltering determination, was decisive in this situation.

On 28 January 1918, Svinhufvud and the other Senators who were in hiding issued a statement:

“Some Finnish citizens, incited by a few power-hungry men and leaning on foreign forces and bayonets, have launched a violent rebellion against the Finnish Parliament and the legitimate Government, thus putting in jeopardy the newly-won liberty of the Fatherland. The Government has considered itself forced to put an end to this treachery by all possible means. To that end, the law-enforcement troops which, by virtue of the mandate of the Parliament, have been established to maintain order in the country, are thus subjected to centralised leadership, and General G. Mannerheim has been appointed as their commander…”

Legitimate government defeats rebellion

Svinhufvud asked Germany and Sweden to intervene. During the rebellion, the reds ransacked Svinhufvud’s home, Kotkaniemi, in Luumäki. At the beginning of February, Svinhufvud tried to escape from the Red Helsinki by plane, but the attempt failed and he had to return as the engine of the plane went out after half a mile’s flight. At the beginning of March, Svinhufvud finally managed to escape from Helsinki. He sailed to Tallinn on icebreaker Tarmo, which had been commandeered by the White Guard, and from Tallinn he continued to Berlin.

A few days before the arrival of Svinhufvud, Edvard Hjelt, the Finnish ambassador to Germany, had signed agreements by which Finland was militarily, politically and economically tied to Germany. Svinhufvud’s role in the conclusion of these agreements is unclear, but it is likely that he knew and accepted the contents of the agreements. It had long been Svinhufvud’s opinion that Finland must receive help from Germany at any price to run the Russian troops out of the country and defeat the rebellion.

During the War of Independence (to liberate the country from Russian troops) and the civil war to defeat the rebellion, a disagreement broke out between Senate Chairman Svinhufvud and Mannerheim, the commander-in-chief of the government troops, about the interpretation of the martial law. Svinhufvud could not accept the Martial Law of 1909 because, in his opinion, it had been passed in an illegitimate order. Mannerheim, on the other hand, regarded that the martial law was legally in force. As a result of the conflicting views, the situation in the territories recaptured by the government troops was somewhat confusing, as the military commandant and the civilian administration exercised power in parallel.

Even before the events of December 1917 in Finland, the German war regime had decided to detach Finland from Russia, the real objective being economic benefits. Germany did not consult the Finnish government or the head of state as it took the decision in February 1918 to send a military expedition to Finland. Finland’s request for assistance was only a formality, but it was in line with the aspirations of Finland’s political leadership.

The Baltic Sea Division, led by General Rüdiger von der Goltz, landed in Hanko at the beginning of April and liberated Helsinki on 13 April. Another German expedition expelled from Åland Islands the Swedish troops that were trying to annex the island group to Sweden. A third German expedition landed in Loviisa and cut off the railway line to St. Petersburg and captured Lahti, speeding up the process that led to the end of the civil war.

In a decisive victory, the government troops, under the leadership of Mannerheim, had already captured Tampere after heavy fighting. The victory parade, led by General Mannerheim, was held in Helsinki on 16 May.

After the rebellion, the government army was left to deal with some 80,000 prisoners, including many red leaders and suspected leaders. At first, they were tried in army field courts. Death sentences were not uncommon. Svinhufvud had always been an ardent supporter of the rule of law. He felt that all prisoners should be given a fair trial. As a result, 140 special tribunals and a court of appeal were set up. They dealt with 75,575 cases, leading to 67,788 convictions. The courts ordered 555 death sentences (0.8 per cent of the convictions). Of those who had received the death penalty, 113 were executed. Many people died in the prison camps. In the autumn, Svinhufvud pardoned most of the prisoners and at the end of the year there were about 6,000 prisoners left. The rebellion cost the lives of more than 36,000 people. The aftermath of the rebellion left a deep dividing line in Finnish society.

Svinhufvud becomes holder of supreme power

The violent events of autumn 1917 and spring 1918 changed Svinhufvud’s attitude to the form of government. The former republican and believer in peaceful resistance through judicial means became a supporter of strong leadership and a monarchist in favour of power politics. Svinhufvud’s own position changed when the parliament elected him on 18 May as the “holder of supreme power” (State Regent). The supreme power was transferred from the parliament to the Senate Chairman, P. E. Svinhufvud. Thus he became the first head of state of independent Finland.

In the debate preceding the decision, it was discussed whether the supreme power should be given to Svinhufvud in his position as Senate Chairman or as a person. The latter position won.

It was somewhat a paradox that the extensive, partly non-parliamentary powers were given to Svinhufvud of all people. In 1917, nobody wanted a non-parliamentary, autocratic head of state like the emperor, least of all Svinhufvud.

As Svinhufvud became Chairman of the Senate, a Vice-Chairman needed to be elected, who had the actual leadership of the government. It was later established as a practice that Svinhufvud would formally make his decisions at the government sessions, but otherwise he would not attend them. Basically, the Senate dealt with all matters except for the appointments to the highest posts, the approval of bills and laws, and pardons. The area where Svinhufvud had most power was foreign policy, which was the responsibility of the head of state.

Svinhufvud’s choice for the Senate Vice-Chairman (Prime Minister) was J. K. Paasikivi, Director General of Kansallis-Osake-Pankki and the strong man of the monarchist wing of the Old Finnish Party. Otto Stenroth, a bank manager, was appointed Finland’s first foreign minister. Independent Finland’s foreign policy now had four leaders: Svinhufvud, who was State Regent, Prime Minister Paasikivi, Foreign Minister Stenroth, and, finally, Wilhelm Thesleff, who had been appointed War Secretary and commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

As State Regent, Svinhufvud aimed to establish strong ties between Finland and Germany – in an attempt to protect the country against the Soviet threat. The most important thing was to maintain the military alliance. The Baltic Sea Division remained in Finland. There were also plans to make Finland a kingdom ruled by a German king. In August 1918, Svinhufvud and Foreign Minister Stenroth traveled to Germany to meet Emperor Wilhelm and the German foreign minister. At that time it looked like Germany would win the war, thanks to its successful Spring Offensive.

The Emperor did not promise his son Prince Oskar to be king of Finland but, instead, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse was elected to the throne in early October. However, as Germany suffered a defeat in the World War a month later, the king renounced the crown and Finland started to distance itself from Germany.

In foreign politics, Svinhufvud was a determined and straightforward leader, but he also acknowledged the realities. His policy had come to a dead end. The Paasikivi Senate resigned on 27 November 1918. The Senate of Lauri Ingman, from the Old Finnish Party, worked hard to get Britain and the United States to recognise Finland’s independence. Svinhufvud continued as State Regent until 12 December, but in his letter of resignation he requested that he should be succeeded by General Mannerheim, who was known for his good relations with the West.

Epitome of national defence

After retiring from governmental duties, Svinhufvud served for a few years as Managing Director of Suomen Vakuus Oy, a credit institution established in Turku, but the company was not successful. After that, Svinhufvud withdrew to his home, Kotkaniemi, to enjoy his retirement days on a pension granted to him by the State.

Svinhufvud had joined the Civil Guard (“White Guard”) already during the time he spent in Turku. In Luumäki, it became his main pastime. In five years, he rose in the ranks from a private to a sergeant-major. He also participated in the administration of the organisation. An old hunter, he took up shooting practice, becoming a successful competitive marksman. Svinhufvud became the epitome of the national defence of the young Republic , the folksy “Ukko-Pekka” in his Civil Guard uniform and a rifle on his shoulder, whose personal example strongly influenced the expansion of the Civil Guard. In his view, the safeguarding of Finland’s independence required that the country’s entire non-leftist population participated in the strengthening of the national defence.

Svinhufvud was a rank-and-file member of the National Coalition Party established in the autumn of 1918. The party named him as a candidate for the 1925 presidential election, in which he received 68 electors. But when it began to look probable that he would have no chance of winning a majority of the electorate (at least 151), the party’s electors decided to vote another candidate of the party, party Chairman Professor Hugo Suolahti, already in the first round.

The anti-communist Lapua movement was born in 1929. The popular movement, which desired a stronger government, contributed to the rise of P. E. Svinhufvud as Prime Minister at the beginning of July 1930. Just a few days later, the Lapua movement organised its most prominent show of force, the 12,000-strong Peasant March to Helsinki.

The Lapua movement gradually started to resort to lawlessness, such as capturing, assaulting, and murdering suspected communists. The illegal activities culminated in the abduction of K. J. Ståhlberg on 14 October 1930. Ståhlberg, who had been President of Finland in 1919–1925, and his wife were abducted near their home in Kulosaari, Helsinki, forced into a car and driven to Joensuu. In Joensuu, the abductors waited for another transport, but when it did not come, they released their prisoners.

Right from the start, Svinhufvud had distanced himself from the lawless methods of the Lapua movement, seeking to restore the authority of the lawful government, even though he approved of the anti-communist goals of the popular movement. Svinhufvud was elected President of Finland in February 1931. The Agrarian League did not want to support L. Kr. Relander for a second term, but voted for Svinhufvud instead. In those restless times, Svinhufvud was considered a stronger leader than K. J. Ståhlberg, who was supported by the Social Democrats.

One of Svinhufvud’s first acts as President was to organise the leadership of the Armed Forces by appointing General Mannerheim, who had retired from the military 13 years earlier, as Chairman of the reformed Defence Council.

The Mäntsälä rebellion

Right-wing protesters, gathering in Mäntsälä, 50 kilometres north of Helsinki, demanded that communist and social democratic parties should be banned. They presented their ultimatum to the government on 28 February 1932: “Marxism must be overthrown, and it will be overthrown, even if we first have to overthrow the government and its representatives who support it.”

Within the government, there were mixed feelings about the imminent right-wing rebellion. Some wanted to crush the rebellion with arms, some were inclined to agree to the demands made. President Svinhufvud wanted to resolve the crisis by peaceful means, but resolutely and without dissolving the government. His famous statement to the military leadership was: “Not a single armed man may come from Mäntsälä to the Capital. That is for you to make sure, Generals.”

The government’s actions and the declaration given in the name of the President did not have the desired effect. Instead, more and more armed men from all over the country were arriving in Mäntsälä – and still more were planning to go. It has been estimated that there soon would have been an armed force of several tens of thousand men assembled in Mäntsälä ready to march to the capital. The danger of a civil war was imminent. In Italy, Benito Mussolini had made his fascist coup just in this way (the March on Rome).

On 2 March 1932, the government put President Svinhufvud in charge of defeating the rebellion. The President set up special headquarters consisting of the Defence Minister, the Chief of Defence, the Commander of the Civil Guard, and the Inspector of the Infantry from the General Staff. However, Mannerheim, who was Chairman of the Defence Council, refused to join the headquarters, thus expressing indirect support for the rebels. The activists’ preparations to make Mannerheim the dictator of Finland were nearly completed.

In this extremely precarious situation, Svinhufvud made a speech on the radio, written by T. Kivimäki, the Minister of Justice, in which he appealed to the members of the Civil Guard and urged them to return to their homes. The radio speech had the desired effect and the rebellion dried up.

Svinhufvud’s radio speech can be compared to the declaration he issued from his secret hiding place in “Red Helsinki” in January 1918. The message was the same: the parliament and the legitimate government, which enjoys the parliament’s confidence, shall not be overthrown by unparliamentarian means. Lawful democratic order shall be safeguarded even by armed forces, and even at the risk of civil war.

The situation during the Mäntsälä rebellion was extremely grave, because the loyalty of the Civil Guards to the government was hanging in the balance and depended now solely on the credibility and strength of the president. The difference to the rebellion of 1918 was that now Svinhufvud had to defeat the unparliamentary pressure and revolt emanating from circles that were close to his own political home. His widely acknowledged career in the Civil Guards, as well as his reputation as a fine marksman, lent credibility to his appeals for a peaceful solution.

President Svinhufvud’s speech did the trick. Members of the Civil Guards on their way to Mäntsälä turned on their heels and returned home. The leaders of the rebellion were captured. After defeating the rebellion, Svinhufvud forced the commander of the Civil Guard, Lauri Malmberg, to take a year-long leave for “studies”. He also transferred Aarne Sihvo, the Chief of Defence, to the Ministry of Defence. Svinhufvud’s personal courage, determination and authority saved Finnish democracy. Finland remained a democracy during a critical period when in many other European countries democracy had been shaken and the countries had moved to full or partial dictatorships.

President’s government and the Nordic trend

After the defeat of the rebellion, Svinhufvud was in charge of the country’s foreign policy and to a large extent the internal affairs as well. He appointed a minority government with Kivimäki as PM. It was a so-called president’s government. The Kivimäki government enjoyed the parliament’s confidence for almost four years, which was a considerable improvement in parliamentary stability, as the previous record had been less than two years. The political tensions in the country eased and the economic crisis was followed by a strong upswing. The president succeeded in leading the country from the brink of civil war to normality, both politically and economically.

In foreign politics, Svinhufvud led Finland to Nordic co-operation and neutrality. He did not make formal state visits, but strengthened the Finnish ties with Estonia and Sweden through informal visits.

After the parliamentary election in 1936, Svinhufvud did not accept the Social Democrats in the government, even though the party was clearly the largest in the country and had 83 seats in the 200-seat parliament. Svinhufvud argued his position with the Marxist nature of the Social Democratic Party’s programme and their class struggle rhetoric, but more than this, his position was influenced by the 1918 rebellion and the oversized programme of Väinö Tanner’s Social Democratic minority government of 1926–1927 and the party’s dismissive attitude to national defence. With the SDP against him, Svinhufvud lost the 1937 presidential election.

He once again retired to Kotkaniemi and became a private citizen. However, towards the end of the Winter War, in the spring of 1940, Svinhufvud traveled to Germany to get support for Finland. Germany had surrendered Finland to the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. Hitler would not see him, and neither would Mussolini in Rome. Instead, Svinhufvud met Pope Pius XII.

During the Continuation War which began in 1941, Svinhufvud authored a National Programme, printed in the autumn of 1943 as a small edition. The pamphlet dealt with the creation of Greater Finland through active warfare. A speaker at Svinhufvud’s funeral in January 1944 emphasised a resolute attitude towards the Soviet Union, which Prime Minister Edwin Linkomies regarded as an inappropriate demonstration in the midst of peace talks.

Svinhufvud’s legacy

Svinhufvud’s social views, his sense of justice, his powers of discernment, and his down-to-earth nature were all inherited from the old rural judges and magistrates. Behind the folksy figure of “Ukko-Pekka”, which he adopted at mature age, Svinhufvud was a shrewd lawyer with a clear view of the political big picture and tactical ability to get results in a multiparty democracy.

Svinhufvud was a reformist. In his opinion, a strong state was needed to uphold national defence and the rule of law, but also to overcome social disadvantages.

Svinhufvud’s political leadership was initially based strictly on principles, but with government experience it became more pragmatic. As a sociable person, he managed to win support from different groups and enjoyed genuine popularity among the people. Svinhufvud’s leadership was based on his great personal charisma and trust that he inspired in people.

Svinhufvud’s leadership was marked by personal courage. He fearlessly defended the principles he considered right, even though the price was being twice dismissed from his position as a judge and deportation to Siberia. He was also willing to step down when circumstances changed, as in December 1918. He certainly cannot be blamed for clinging to power.

For Svinhufvud, the Finnish state’s independence and liberty, the rule of law and democracy based on free elections were inalienable core values. As Speaker in the first five years of the Parliament, he established the solemn style in which the Parliament was to be chaired. Svinhufvud’s practical leadership became apparent as he was Prime Minister of the government that declared Finland independent and the first head of state of independent Finland in 1917–1918, and as Prime Minister for the second time and as President of the Republic in 1930–1937. Thanks to his moral strength and personal courage, two rebellions against the legitimate government were defeated and the rule of law and democracy survived.